Red cells, space skin & Himalayan DNA: Malta's leap into space medicine

From red cells in orbit to DNA in the Himalayas, Prof Joseph Borg is spearheading Malta's most ambitious space bioscience programme. In this special Techmag feature, we explore three groundbreaking research missions that blend medicine, genomics, and planetary science, pushing Maltese science to the edge of space and beyond.

The future of medicine might not lie in the corridors of a hospital, but in orbit, on mountaintops, and inside the microscopic building blocks of life. At the forefront of this shift is Prof. Joseph Borg, a scientist whose vision has propelled Malta into the international spotlight of space bioscience.

In partnership with institutions like NASA, ESA, ISRO, and SpaceX, Prof Borg and his team at the University of Malta have led three extraordinary missions that fuse high-altitude biology, astronaut health, and microbial genomics.

The Maleth Trilogy sent diabetic skin tissue to the International Space Station to study how bacteria behave in microgravity. The Space Anaemia Project used astronaut blood and stem cell models to decode how space weakens red blood cell production. And most recently, a daring field expedition to Ladakh, India, tested real-time DNA sequencing at 5,000 metres, simulating Mars-like conditions.

Each project carries local relevance, addressing conditions like β-thalassaemia and diabetic ulcers, while feeding global research into astronaut safety, personalised medicine, and space exploration readiness. Together, these missions position Malta not as a bystander but as an active contributor to the biology of the final frontier.

The Maleth Trilogy – Uncovering the invisible battle on human skin

What if the answers to some of Earth's most stubborn medical mysteries could be found, not under a microscope in a traditional lab, but orbiting hundreds of kilometres above us, in the weightlessness of space?

That bold idea was the seed behind Malta's first-ever space bioscience experiment: The Maleth Project. What began in 2021 as a vision to understand how bacteria behave in space rapidly expanded into a trilogy of space missions, Maleth I, II, and III, spanning over three years and becoming a cornerstone of Malta's scientific footprint in orbit.

Maleth III – Maltese Experiment ready for the ISS

At the heart of this initiative was an important life science topic: human skin tissue. Specifically, skin biopsies were taken from patients suffering from diabetic foot ulcers, one of the most painful and difficult-to-treat complications of diabetes. These samples were carefully packaged, preserved, and launched into orbit aboard SpaceX missions to the International Space Station (ISS).

Their goal? To study how microbiomes, the microscopic communities of bacteria and fungi that live on our skin, change when exposed to spaceflight conditions such as microgravity, radiation, and confinement.

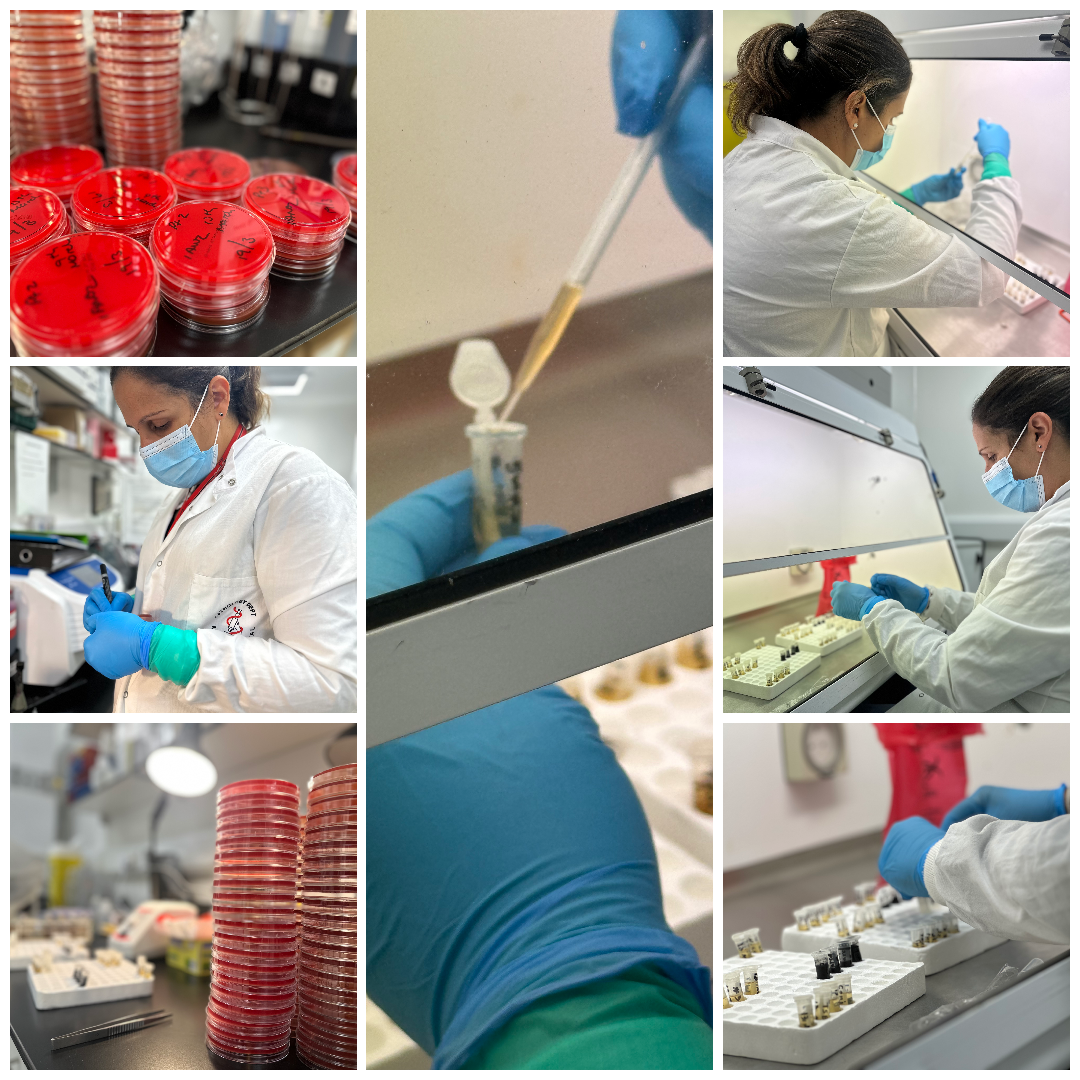

The scientific mission was led by Ms Christine Gatt, a biomedical laboratory scientist working at the bacteriology lab of Mater Dei Hospital and a PhD student at the University of Malta. Her work, carried out in collaboration with a team of national and international partners, was not just about sending samples to space; it was about bringing knowledge back to Earth.

Why microbiomes? Why skin?

Let's take a step back. Our skin is not just a protective barrier; it's a living, breathing ecosystem. Every square centimetre is colonised by hundreds of species of bacteria, fungi, and viruses that play vital roles in immune defence, wound healing, and maintaining healthy skin function.

Ms Christine Gatt, lead scientist, biomedical laboratory scientist at Mater Dei Hospital, PhD student at University of Malta

In people with diabetes mellitus, however, this microbial balance is often disrupted. The immune system becomes less effective, wounds heal more slowly, and specific pathogens, especially antibiotic-resistant ones, can take over. Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), in particular, are a major clinical challenge. They can persist for months, recur frequently, and sometimes lead to amputation.

Microbiome research has already shown that chronic wounds have a unique microbial signature, one that often correlates with poor outcomes. But until now, researchers had limited ability to manipulate or deeply understand how the microbiome behaves under unusual environmental stresses.

That's where spaceflight enters the picture.

The view from orbit: Space as a microbial stress test

Space presents a unique laboratory. Conditions such as microgravity, radiation, altered atmospheric pressure, and isolation from Earthly contamination create a perfect storm to study microbial behaviour. Microorganisms, just like humans, undergo physiological changes in space.

The Maleth mission capitalised on this. Skin tissue from DFUs was collected from consenting patients at Mater Dei Hospital, cryopreserved, and loaded into biocube payloads developed in partnership with Space Applications Services (Belgium) and SpaceX. These biocubes were engineered to keep the tissue sterile and viable, simulating clinical wound conditions while in orbit.

Maleth I launched in August 2021 aboard SpaceX CRS-23. Maleth II and III followed in 2022 and 2023, respectively. Each mission lasted approximately 30 days on the ISS, orbiting Earth over 400 kilometres above sea level. Back on Earth, matched control samples were kept in identical conditions. The key difference? One batch was influenced by gravity and Earth-based microbes; the extreme and alien environment of space shaped the other.

What did we learn?

When the space-flown samples returned to Malta, the real work began. Using a combination of bacterial culture, microscopy, and next-generation DNA sequencing, the team compared the microbiomes of the Earth-bound and space-exposed skin samples.

The results, some of which were recently published in the journal Heliyon[see https://www.cell.com/heliyon/fulltext/S2405-8440(22)03363-1], were remarkable.

Microgravity appeared to promote the overgrowth of certain opportunistic and antibiotic-resistant bacteria, while suppressing others. Strains like Staphylococcus epidermidis and Enterococcus faecalis became more dominant, suggesting that space may reduce microbial competition or immune-like regulation, allowing these organisms to flourish. Importantly, spaceflight seemed to alter not just which bacteria were present, but how they behaved. Genes associated with virulence, biofilm formation, and resistance to antibiotics were more highly expressed in the space samples. This aligns with other NASA research showing that some bacteria, like Salmonella, become more infectious in microgravity.

The implications of these findings are twofold:

For astronauts: Understanding how bacteria change in space is critical for long-duration missions. If specific pathogens become more aggressive or resistant in orbit, they could pose significant risks to astronaut health during missions to Mars or the Moon.

For patients on Earth: The insights gained from these microbial shifts may help predict or manage chronic infections, especially in diabetic patients. If we can identify "space-like" stress conditions that reveal bacterial weaknesses or strengths, we may design better therapies and wound treatments.

A Maltese milestone in space science

The Maleth trilogy wasn't just a scientific experiment; it was a national milestone. For the first time, Maltese biomedical samples were part of an international spaceflight study. The project was supported by the Government of Malta, the University of Malta, and international collaborators from the ESA and NASA networks. It also marked Malta's inclusion in global initiatives like the Space Omics and Medical Atlas (SOMA) project.

Skin tissue sampling

In addition, Maleth helped establish Malta's first national microbiome database, with complete genomic datasets available for local and international researchers. These datasets represent an invaluable resource for studying chronic wounds, antibiotic resistance, and personalised medicine.

The legacy of Maleth

Maleth was not just about exploring science in space; it was about pushing boundaries at home.

It empowered local researchers like Ms Christine Gatt to operate on a global scientific stage, trained a new generation of biomedical students in astrobiology, genomics, and translational medicine, and inspired public interest in the role of space in solving Earth-based problems. Looking ahead, the team plans to expand Maleth into other tissue types, oral mucosa, conjunctiva, and even gut biopsies using minimally invasive sampling and more real-time in-orbit analytics.

The final takeaway? Space isn't just a place for rockets and robots. It's a frontier where the smallest organisms, the bacteria on our skin, can teach us the biggest lessons about life, health, and healing.

And Malta, through the Maleth trilogy, has boldly taken its place in that journey.

Red cells in orbit: Cracking the code of space anaemia

Blood. It courses through our veins, delivers oxygen to our tissues, and sustains our very existence. But what happens to blood when we leave Earth?

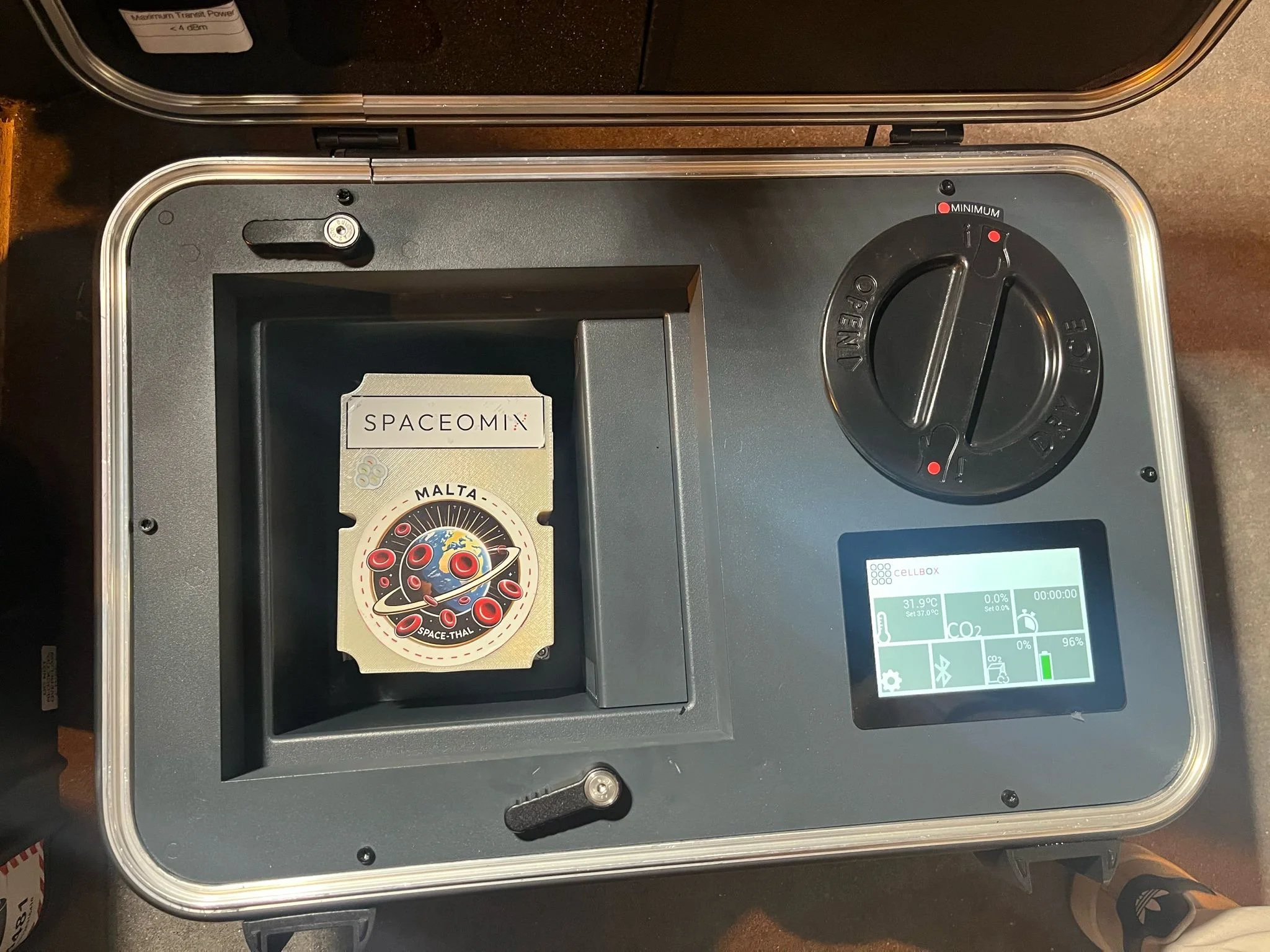

In a series of groundbreaking experiments, our team at the University of Malta and Spaceomix Ltd., in partnership with SpaceX, NASA Gene Lab, and international collaborators, has been investigating a curious and potentially dangerous condition known as space anaemia. This drop in red blood cell count during spaceflight has been observed in astronauts for decades, but only now are we beginning to understand why it happens and how we might fight it.

What makes this story even more exciting? It's a mission that involves human astronaut blood, stem cell models in orbit, and a dedicated Maltese research team, including Dr Josef Borg (postdoctoral fellow), Ms Maria Vella (PhD student), and Mr Aidan Borg (BSc student), all pushing the boundaries of space medicine from our small island to the stars.

Ms Maria Vella (PhD student), Dr Josef Borg (postdoctoral fellow) and Mr Aidan Borg (BSc student)

What is space anaemia?

First reported in the early days of space exploration, space anaemia describes the body's tendency to destroy red blood cells faster than it can produce them while in space. This leads to a reduction in oxygen-carrying capacity, leaving astronauts fatigued, short of breath, and potentially at risk during high-stakes missions. For long-duration journeys such as those planned to Mars or deep space, this becomes a serious concern. If we are to survive and thrive beyond Earth, we must first understand how our bodies react to life in orbit.

Our team tackled this challenge using a dual approach:

In vitro models: Growing human stem cells (from bone marrow, cord blood, and peripheral blood) in special payload biocubes exposed to spaceflight or space-like conditions.

Astronaut blood analysis: Examining real blood samples from astronauts before launch, during flight, and after returning to Earth.

Together, these studies provide a complete picture of how erythropoiesis, the production of red blood cells, is influenced by space changes.

The stem cell payloads: Growing blood in microgravity

To replicate the body's blood factory outside the body, we cultured stem cells in bioreactors designed to simulate space conditions. These payloads, developed in collaboration with international partners, mimic microgravity, altered oxygen levels, and cosmic radiation exposure.

Each payload included carefully prepared samples of Cord blood stem cells (neonatal origin), Peripheral blood stem cells (from healthy adults) and Bone marrow stem cells. Inside the sealed units, these cells were coaxed to differentiate into red blood cells, a process requiring oxygen sensing, iron metabolism, and tightly controlled gene expression.

We examined key regulatory genes such as KLF1, BCL11A, and MYB transcription factors known to control the switch from foetal haemoglobin (HbF) to adult haemoglobin (HbA). Understanding this switch is critical, not just for space health, but for treating genetic diseases like β-thalassaemia and sickle cell disease, both of which remain public health challenges in Malta and worldwide.

The astronaut samples: Blood across the timeline

While the stem cell models offered a test-tube simulation, nothing compares to the real thing. As part of a collaborative research initiative with SpaceX private missions and other commercial astronauts, we received astronaut blood samples at three crucial timepoints:

Preflight: Several weeks before launch

Inflight: While orbiting Earth aboard SpaceX missions

Return: Within days of landing

Each sample was processed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to separate and quantify different haemoglobin types: HbF (Foetal Haemoglobin): Dominant in the womb, suppressed after birth, HbA (Adult Haemoglobin): Normal in healthy adults and HbA2: A minor adult variant.

Our Nature Communications publication in 20241 reported an intriguing observation: astronauts showed a measurable increase in HbF during spaceflight, followed by normalisation post-return. This suggests a reactivation of foetal haemoglobin, likely triggered by the stress of microgravity, radiation, and confined living.

Such reactivation may be the body's attempt to adapt to protect red cells, enhance oxygen delivery, or compensate for reduced erythropoiesis. It opens a door to therapeutic HbF induction as a countermeasure for space anaemia.

A Maltese team at the forefront

This research wasn't conducted in isolation. Our team, including me, Dr Josef Borg, and students Maria Vella and Aidan Borg, participated hands-on in every stage. In March 2024, the team travelled to Florida, USA, for a packed itinerary. First stop: Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, where our payloads were tested and integrated. The team ensured sterility protocols and handled astronaut blood under strict biosafety conditions.

Then came the emotional high: attending the SpaceX launch at Kennedy Space Centre. Standing at Playalinda Beach with scientists from the US, Korea, and Saudi Arabia, we watched the rocket carry our samples and our hopes into orbit. For our students, it was a life-changing experience. "Seeing our work leave the Earth was surreal," Maria said. "It gave us a sense of how far Maltese science can go literally."

Inside the haemoglobin switch

At the heart of this research lies the concept of the globin gene switch, the developmental transition from producing HbF to HbA. In patients with β-thalassaemia or sickle cell disease, this switch becomes a liability: their mutated adult haemoglobin causes disease, while foetal haemoglobin is absent.

Reactivating HbF, therefore, is a therapeutic holy grail. Space, it turns out, is a potent biological stressor. The combination of microgravity, oxidative stress, and radiation may disrupt the normal silencing of HbF genes. We suspect this happens via epigenetic changes in the promoters of HBG1/HBG2, or altered regulation by transcription factors like BCL11A, whose repression is key to sustaining HbF expression. In parallel, our single-cell RNA sequencing studies on in vitro payloads are revealing novel insights into how erythroid progenitors respond to space. Some cells show enhanced plasticity, others display delayed maturation, and a subset exhibit HbF re-expression, confirming what we saw in astronaut blood.

Implications for Earth and beyond

The benefits of this work extend beyond the space sector. For patients with haemoglobinopathies, understanding how HbF can be re-induced may guide new therapies. Already, gene-editing platforms (like CRISPR-Cas9) are targeting BCL11A to switch on foetal haemoglobin. Our space data can help optimise these strategies, identifying biomarkers of responsiveness and ensuring safety.

For astronauts, our research supports a move toward personalised medicine in space. Blood monitoring before, during, and after missions can inform diet, exercise, and pharmacological support to prevent anaemia. It could also lead to the development of portable blood diagnostics and even onboard red cell bioreactors for future Mars crews.

Malta's leap forward in space bioscience

Space anaemia is no longer a mystery hidden in orbit; it's a condition we are actively decoding, thanks to a growing body of collaborative research. Malta, through our recent initiatives and related projects, is establishing itself as a serious player in the field of space omics, merging biomedicine, genetics, and bioengineering with global exploration efforts.

By partnering with NASA GeneLab, SpaceX, and ESA's Human and Robotic Exploration Programme, we're not just observing how the human body reacts to space; we're shaping how it survives. And perhaps, in solving how blood changes among the stars, we may discover how to heal those still suffering on Earth.

DNA on the roof of the world – A mission to Ladakh

When we imagine the future of human space exploration, we picture rockets, Martian dust, and astronauts floating in microgravity. But the path to Mars doesn't always begin with a launchpad. Sometimes, it starts with a backpack, a solar panel, and a portable DNA sequencer trekking through the icy winds of the Himalayas.

That was precisely the mission of Dr Anu R I, a clinician-scientist based at the University of Malta, and supported by Spaceomix Ltd., who joined a unique expedition to the Ladakh region of India, a high-altitude desert nestled deep in the Himalayas. Her mission? To simulate a Martian field lab by performing on-site, real-time DNA sequencing on human analogue astronauts participating in a Mars simulation.

India Mission Ladakh region

This extraordinary initiative was part of Spaceward Bound India 2025, a collaboration between the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and multiple international partners to train scientists and students in the techniques required for planetary exploration. Dr. Anu's role focused on a single, powerful question: "Can we test human DNA and microbiome changes, in real time, in extreme environments just like we would need to on Mars?"

Why Ladakh? Why now?

The Ladakh region of northern India is no ordinary place. Perched at over 5,000 meters above sea level, with thin air, extreme temperatures, and arid landscapes, it mimics many of the environmental features of Mars. NASA and ISRO consider it one of the most promising Martian analogue environments on Earth. That makes it an ideal training ground to test life-support systems, space gear, and, yes, biological diagnostics.

Ladakh Region, India

But Ladakh also poses enormous challenges. At that altitude, oxygen levels are nearly 40% lower than at sea level, and the risk of altitude sickness, dehydration, and immune dysregulation is real. Human physiology begins to change in profound ways, and so does the human microbiome, the community of microorganisms that live in and on our bodies.

For astronauts, understanding how these biological changes unfold in real time is essential. If something goes wrong on Mars, say, a gut infection, a viral reactivation, or immune collapse, there won't be time to send samples back to Earth.

This is where portable sequencing becomes a game-changer.

Enter the MinION: DNA Sequencing in the Palm of Your Hand

At the centre of Dr Anu's toolkit was a sleek, portable-sized device called the Oxford Nanopore MinION. It's one of the most compact and robust next-generation DNA sequencers in the world. About the size of a TV remote, it plugs directly into a laptop and can perform whole-genome or targeted gene sequencing in real-time.

Unlike traditional sequencing platforms that require large laboratory setups, the MinION is field-deployable. It works in harsh environments, needs minimal reagents, and doesn't require bulky centrifuges or climate-controlled labs. All it needs is a power source, a clean sample, and a pair of steady hands, exactly what Dr. Anu had packed for her Himalayan expedition.

She was accompanied by human "analogue astronauts" participating in the simulation, trained volunteers mimicking future Martian explorers. These participants would undergo rigorous physical and psychological protocols while living in tents, conducting geological surveys, and navigating extreme terrain, offering the perfect opportunity to study how stress and altitude affect human DNA and microbiomes.

Collecting the data: Saliva, blood, and bacteria

Using field sterilisation kits and portable refrigeration, Dr. Anu collected saliva and blood samples from each participant at three key timepoints:

Pre-mission baseline (before the climb)

Mid-mission (at high altitude in Ladakh)

Post-mission (after descent)

The samples were processed using rapid DNA extraction protocols compatible with the MinION workflow. Within hours, she was able to begin real-time sequencing, even while high up in the mountains and under canvas tents.

The initial goal was twofold: To assess changes in host DNA expression, especially stress-related and immune-regulatory genes and to monitor microbiome composition, particularly in the mouth and gut, to detect dysbiosis (microbial imbalance) caused by altitude and isolation.

What the sequences revealed

Back in Malta, our bioinformatics team are anxiously waiting to analyse the data that is on its way back from Ladakh. We will be on the lookout for upregulation of genes involved in inflammatory response, hypoxia signalling, and oxidative stress, hallmarks of physiological adaptation to altitude. The oral microbiome is also expected to change significantly during the mission. There might be a drop in commensal (beneficial) bacteria and a rise in potential opportunistic species like Prevotella and Fusobacterium.

We shall then examine and interpret these data in conjunction with those of space agencies like NASA, which have observed that real astronauts experience changes in their microbiome due to confinement, stress, altered diets, and environmental pressure, potentially impacting immunity, digestion, and mental health.

Why does this matter for Mars

This wasn't just a fancy field trip with cool gadgets. It was a proof-of-concept mission that tested the future of on-demand space diagnostics.

In the coming decades, astronauts will venture farther from Earth than ever before, first to the Moon, then to Mars, and possibly beyond. On these journeys, there will be no emergency evacuation, no quick access to labs, and no possibility of sending blood samples back home. Space medicine must be autonomous, portable, and robust. DNA sequencers like the MinION could play a central role in diagnosing infections, monitoring genetic health, or even assessing microbial life in Martian soil or water samples.

India's first 'analogue' space mission, Hab-1, was tested in the mountains of Ladakh.webp

Dr. Anu's successful deployment of this technology under real-world stress validates its readiness for space. Oxford Nanopore devices are already part of NASA's Biomolecule Sequencer program and have been tested aboard the ISS since 2016. But what makes this story unique is that a small nation like Malta is now part of that conversation, contributing directly to the frontier of space bioscience.

Lessons from the edge

When asked about her toughest challenge, Dr Anu smiles. "The altitude was brutal," she says. "Every step felt heavy. The cold seeped through everything. But when I saw that first DNA readout pop up on my laptop… out there in the Himalayas, I knew it was worth it."

The expedition also highlighted logistical lessons: the importance of sample stability, low-power equipment, data storage solutions, and bioinformatics workflows that can run offline or on-site. With the support of the University of Malta and Spaceomix Ltd and our wider research network, the data from this mission is now being incorporated into broader studies on microbiome dynamics under stress, alongside samples from spaceflown experiments and analogue missions in other extreme environments, like the Arctic or deserts.

Dr Anu R I with Oxford nanopore minION machine

What's next?

Following this success, we're exploring future deployments of real-time DNA sequencing in: Undersea missions (e.g., NEEMO analogues), Antarctic research stations and Desert space analogues in North Africa.

Dr. Anu is also mentoring a cohort of students in Malta interested in field-based genomics, opening up new career paths that blend medicine, space science, and biotechnology. And, of course, we aim to send the next iteration of this technology back to space, but this time with full integration into onboard astronaut health monitoring systems. Imagine an astronaut on Mars sequencing their gut microbiome or scanning for viral mutations using nothing more than a handheld device.

That future isn't far. It already started on a cold morning in Ladakh, with an Indian scientist representing both the flag of Malta and India, a pocket sequencer, and the courage to push science beyond its comfort zone.

Malta’s surveillance network is growing—CCTV cameras, biometric ID cards, and facial recognition trials—yet there’s little debate or oversight. Manuel Delia investigates how rapid digital transformation is reshaping governance, redefining citizenship, and eroding privacy under the guise of convenience, safety, and technological progress.