Surveilling the Republic: How tech is quietly rewiring our democracy

Malta's quiet surveillance state is expanding—biometric ID cards, ANPR cameras, and facial recognition trials—all introduced with little debate. In this deep dive, Manuel Delia examines how digital transformation is reshaping governance, eroding privacy, and prompting citizens to comply with regulations in the name of convenience, safety, and technological progress.

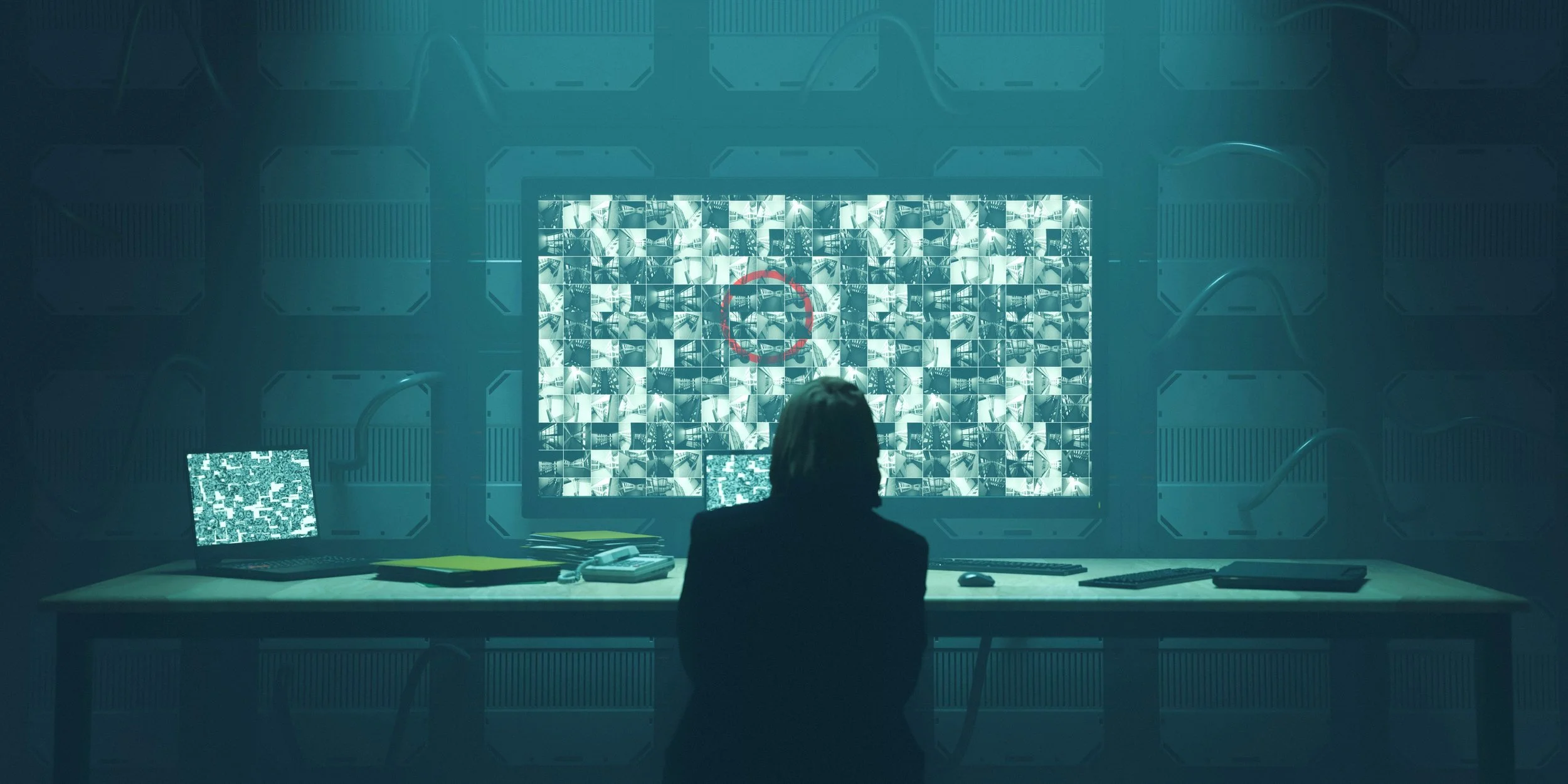

You hardly notice them at first, the cameras perched on traffic lights, school gates, and lampposts. A new mast rises by the village square. Another junction hums with automated enforcement. And your ID card now contains biometric data. In the name of efficiency, safety, and modernisation, Malta is swiftly adopting digital technologies that place citizens under increasingly watchful eyes. But while we marvel at how quickly government services have "gone digital," we rarely pause to ask: at what cost?

In recent years, the government's adoption of surveillance technology has sped up with little public debate. Automated Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) systems now track roads across the country. Facial recognition is quietly being trialled in policing settings. Personal data gathered by one agency is shared freely with others under opaque protocols. These systems are marketed as tools for convenience and safety, but in reality, they are subtly and dangerously transforming the relationship between citizens and the state.

We like to think of democracy as something we build at the ballot box. But in the shadows of digital transformation, democracy is being unbuilt, not with a bang, but with a quiet, relentless blink of the lens.

In 2019, Malta's government proudly announced a partnership with Chinese tech giant Huawei to pilot a Safe City system — a dense network of CCTV cameras equipped with facial recognition, behavioural analysis, and real-time data feeds to law enforcement. Although the project was quietly shelved after public outcry and concerns about China's surveillance exports, its core ambitions remained. They have simply been repackaged and redeployed, piece by piece, under domestic initiatives with much less scrutiny.

Today, cameras are everywhere. Mobile ANPR units can scan hundreds to thousands of licence plates per hour, automatically cross-checking vehicle data with national databases. Municipal councils often install CCTV in public gardens and playgrounds without conducting data protection assessments or consulting the public. Several government offices have introduced biometric systems for staff access control, as confirmed in internal policy guidelines on attendance and security systems. Meanwhile, ID Malta's biometric data management practices, including fingerprint storage, remain largely opaque, with no publicly available audit mechanism in place.

Add to this a growing trend of inter-agency data sharing, often without precise consent mechanisms. Social security data may be accessed by law enforcement under specific legal provisions, though the extent of integration and oversight remains unclear. In line with standard inter-agency data practices, tax information may be cross-checked against vehicle registrations or utility bills, a process often justified as a means of fraud prevention. However, little is publicly disclosed about the oversight mechanisms.

These digital infrastructures are not isolated conveniences; they are part of a larger system. And like all systems, they embody a logic: not of empowerment, but of control.

Behind every surveillance system is a procurement contract, and in Malta, these often raise more questions than they answer. Who supplies the technology? Who maintains it? Who benefits? Government contracts for CCTV installations, biometric ID systems, and traffic surveillance tools are frequently awarded to contractors that operate with minimal public accountability. The value of these contracts can reach into the millions, yet documentation is often unclear, buried in obscure tenders or simply unpublished.

Surveillance infrastructure is often promoted as improving "efficiency." Local councils are told that it will cut vandalism. Enforcement agencies achieve faster fine collection. Ministries talk about "streamlined public service." However, this technocratic language conceals a deeper truth: digitalisation in Malta increasingly serves the interests of the state and its chosen suppliers more than those of its citizens.

Meanwhile, oversight remains alarmingly weak. The Information and Data Protection Commissioner lacks the necessary resources and legislative authority to keep pace with the rapidly advancing surveillance technologies. There is no AI ethics framework, no central audit of data-sharing practices between agencies, and no parliamentary committee with a specific mandate to review surveillance technologies.

In effect, we are building a digital governance system funded by taxpayers, allocated to private actors, and protected mainly from democratic oversight.

Once, citizenship meant agency: the right to participate in public life, to be seen and heard. But as surveillance technologies broaden their reach, citizenship risks being redefined as mere compliance. The citizen becomes a data point: scanned, tracked, and sorted by systems they don't understand and never agreed to be part of.

Take law enforcement. LESA's use of ANPR cameras does more than enforce speeding rules; it creates a real-time map of vehicle movements across the country. The police are exploring facial recognition technology, but there has been no parliamentary debate or legal reform to regulate its use. These tools not only identify violations; they also infer intent, detect patterns, and raise concerns about predictive profiling. On an island where everyone knows everyone, the chilling effect is even more pronounced.

ANPR cameras

Consider also the growing integration of biometric ID into everyday transactions. Access to public services increasingly depends on passive surveillance. There is no real way to opt out. You cannot ask your local council to remove a camera. You cannot tell ID Malta not to store your prints.

In this emerging model of governance, the ideal citizen is constantly visible, documented, and compliant. Anything else – dissent, opacity, anonymity – is regarded as a problem to be controlled.

Despite its broad reach and influence, Malta's surveillance regime has developed almost unnoticed. There has been no national debate, limited media scrutiny, and no parliamentary committee hearings. Civil society has hardly expressed concerns, and politicians, from both sides, refer to digitalisation only in terms of convenience, speed, or "catching up with modernity."

But this is not merely a story of authoritarian intent. It is, more dangerously, a story of democratic neglect. Surveillance has quietly crept in not through grand conspiracies, but through subtle, cumulative decisions, including budget allocations for technology upgrades, outsourcing contracts, and pilot projects with foreign partners, each too small to provoke protest alone, yet collectively transformative.

Our legal framework has not kept pace. Malta lacks a dedicated oversight authority for state surveillance. The Data Protection Act remains focused on bureaucratic compliance rather than democratic accountability. AI systems can be employed in law enforcement without requiring public notification or ethical review.

This lies at the heart of the problem: it's not just that the state is watching — it's that no one is watching the state. And in a democracy, that's supposed to be our job.

We've accepted the digitisation of governance as both unavoidable and harmless — a sign that Malta is progressing. However, not all progress is democratic. Convenience can coexist with control, and innovation can serve those in power just as easily as it serves the people.

What's missing isn't just regulation; it's imagination. We have yet to envision what a rights-based, transparent, and accountable digital state could be. That conversation needs to begin now.

The Democratic Vision 2050, published by Repubblika, offers a starting point. It calls for a future where "digitalisation and surveillance technologies must be designed around fundamental rights and democratic values". It insists that "the use of technologies by government should be fully transparent, subject to democratic oversight, and legally accountable." The document frames this not as a technical debate, but as a democratic one: "There must be constitutional limits to the power of the state in the digital sphere, and enforceable safeguards for the rights of citizens, including the right to privacy."

We don't have to choose between technology and democracy, but we must acknowledge that without deliberate safeguards, the former could quietly erode the latter.

A republic is more than just a government. It is a shared trust, a space for visibility and voice. If we are building a digital state, let it be one where the citizen holds the watch. A state that watches more than it listens is no longer a democracy. It is something else entirely.

Malta’s surveillance network is growing—CCTV cameras, biometric ID cards, and facial recognition trials—yet there’s little debate or oversight. Manuel Delia investigates how rapid digital transformation is reshaping governance, redefining citizenship, and eroding privacy under the guise of convenience, safety, and technological progress.